BICO News Feed

- December 9, 2024

- 1:16 pm

Advanced Techniques for Isolating Rare Microbiota in Complex Samples

Rare microbiota isolation has been instrumental in driving groundbreaking innovations in healthcare, biotechnology, and beyond. From the accidental discovery of penicillin to modern breakthroughs like CRISPR, cultivating microorganisms continually revolutionizes many industries. Less than 1% of environmental microbes have been cultured to date, leaving room for even greater discoveries and innovations in the future (Yu et al., 2022). Advancing our understanding of rare species could lead to new therapies, industrial applications, and insights into ecological systems. This blog explores the importance of studying rare species, the methods used to study them, and the technologies shaping the future of microbiome research.

The Importance of Studying Rare Species

The isolation and cultivation of microbial species have led to some of the most important innovations in healthcare and beyond. For instance, penicillin was accidentally discovered when Alexander Fleming observed that a mold, Penicillium notatum, produced a substance that killed surrounding bacterial colonies (Gaynes, 2017). More modern technologies arising from the isolation and study of microorganisms include CRISPR, which was originally identified as part of a bacterial immune response (Hossain, 2021).

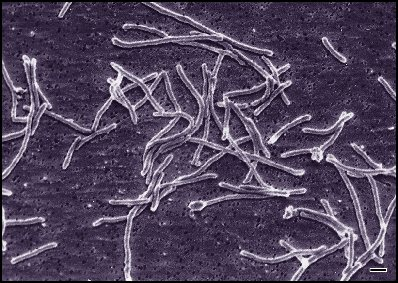

Compounds historically used as cancer therapies and with applications in biological research and agriculture include Actinomycin D and rapamycin, both of which were initially derived from microbes (Demain & Sanchez, 2009). The latter was isolated from microbial species on Easter Island, and its name comes from “Rapa Nui,” which is both the name of the island and the Polynesian language spoken there. Biologists will be familiar with the bacterium Thermus aquaticus, from which thermostable DNA polymerases used in modern PCR reactions are taken (Raghunathan & Marx, 2019)(

Fig. 1).

The isolation and cultivation of rare microbial species have resulted in some of the most significant discoveries in recent years. These breakthroughs underscore the vast potential for uncovering additional applications of microbial species that have yet to be characterized. It is estimated that less than 1% of environmental microbes have been cultured, leaving a massive scope for potential discoveries (Yu et al., 2022).

Challenges in Microbe Isolation

Although isolating and studying rare microbial species is crucial, several significant challenges make species difficult to isolate, which slows the progress of research and development initiatives.

Time Consuming

Traditional methods of isolating and quantifying viable bacteria are often time-consuming and require manual handling of large bacterial populations, increasing the risk of contamination and mislabeling (Franco-Duarte et al., 2019; Needs et al., 2021). Bacteria with similar characteristics in culture can be easily confused, further complicating and prolonging the isolation process.

Specific Growth Requirements

Many microbes are difficult to culture once taken from their typical growing environment.

This is partly because the factors necessary for their growth are poorly understood. These factors may include the presence of other species with which they share a symbiotic relationship, as well as a complex interplay of conditions such as pH, temperature, oxygen levels, and other variables (Gupta et al., 2017).

Low Abundance

Much of microbial research requires the isolation of individual microbes from complex microbiome samples. Less abundant microbes can be difficult to isolate, particularly with manual methods, where they may be overgrown by more abundant or faster-growing microbes (Cena et al., 2021; Han & Vaishnava, 2023). Some species are inherently slow-growing, making it difficult to culture them for characterization studies.

Effective Cell Detection

Microbes are incredibly small, and detecting them with acceptable throughput and precision remains a significant challenge in microbial isolation. Traditional methods often lack the sensitivity needed to reliably identify and isolate individual microbes, particularly in complex samples. Additionally, isolating microbes under anaerobic conditions further complicates detection (Börner, 2016). Many existing technologies for isolating microorganisms are not optimized for these environments, limiting their effectiveness when handling oxygen-sensitive species or those with unique environmental requirements.

Analysis Techniques

The analysis of microbial samples is important for characterizing newly discovered species and for gaining insights into the constituent species of a specific microbial community, such as those found in the human gut, soil, oceans, and other environments. This information helps to understand their roles, interactions, and contributions to ecosystem functions, as well as their potential applications in healthcare and other industries.

Culturing and Microscopy Approaches

Many microbial species can be identified by the different characteristics they display when grown on agar plates, such as colony morphology, color, and growth patterns. These approaches can also include growing microbes on selective media plates or liquid cultures that preferentially promote the growth of certain species. These are known as enrichment cultures. Microscopy can be performed on cultured bacteria and typically involves the application of different stains, such as gram staining, to identify different subgroups (Franco-Duarte et al., 2019; Paray et al., 2023).

Biochemical Assays

These approaches aim to differentiate microbial species based on their ability to metabolize different molecules. This typically involves testing for the presence of certain enzymes like catalase, the ability to ferment sugar, and other metabolic processes like nitrate reduction (Franco-Duarte et al., 2019).

Molecular Techniques and Omics

These techniques include advanced genome sequencing, which offers both high throughput and high resolution for identifying different species. Single-cell and shotgun approaches allow for a focused examination of specific species or a general overview of microbial populations within a particular sample, respectively (Franzosa et al., 2015).

Emerging Technologies

Several important technologies are emerging to address challenges in modern microbiology workflows, collectively allowing for higher throughput and better resolution for studying and culturing novel and rare species.

Microfluidics

Advances in microfluidics have allowed for faster and more accurate rare microbiota isolation. This is particularly powerful when isolating single cells from complex microbiome samples. Microfluidics can provide individual culture environments for single cells, allowing massive throughput at small scales. Microfluidics can also enable the study of interactions between different species, offering greater insights into how microbes fit within their ecological niche (Song et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2022).

Automation and Culturomics

Automation is transforming many industries and is particularly powerful for driving faster and more accurate microbiological workflows. Automation eliminates the need for manual manipulation of bacterial cultures, which is time-consuming, prone to contamination, and incompatible with the isolation of novel species. Recent advances combine automation, AI, and genetic testing into culturomics to isolate and culture specific genera with high throughput (Huang et al., 2023).

The B.SIGHT from CYTENA provides automated dispensing of single microbial cells, allowing for rapid seeding into 96- and 386-well plates (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

Exploring rare microbial species has the potential to unlock unparalleled opportunities for innovation across healthcare, biotechnology, and environmental sciences. Despite the challenges of culturing and studying these organisms, emerging technologies such as microfluidics and automation pave the way for faster discoveries. As we push the boundaries of microbial research, the diversity of uncultured microbes offers a reservoir of potential for transformative solutions. By investing in these advances, researchers can take a significant step toward uncovering the next microbe-derived innovation.

Ready to take the lead in microbiome research? Contact a member of the CYTENA team today to learn more about the B.SIGHT and how it can transform your rare microbiota isolation workflows.

References

- Börner, R.A. (2016) ‘Isolation and Cultivation of Anaerobes’, in R. Hatti-Kaul, G. Mamo, and B. Mattiasson (eds) Anaerobes in Biotechnology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 35–53. Available at:

- Cena, J. A. D., Zhang, J., Deng, D., Damé-Teixeira, N., & Do, T. (2021). Low-Abundant Microorganisms: The Human Microbiome’s Dark Matter, a Scoping Review. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 11, 689197.

- Demain, A. L., & Sanchez, S. (2009). Microbial drug discovery: 80 years of progress. The Journal of Antibiotics, 62(1), 5–16.

- Franco-Duarte, R., Černáková, L., Kadam, S., S. Kaushik, K., Salehi, B., Bevilacqua, A., Corbo, M. R., Antolak, H., Dybka-Stępień, K., Leszczewicz, M., Relison Tintino, S., Alexandrino De Souza, V. C., Sharifi-Rad, J., Melo Coutinho, H. D., Martins, N., & Rodrigues, C. F. (2019). Advances in Chemical and Biological Methods to Identify Microorganisms—From Past to Present. Microorganisms, 7(5), 130.

- Franzosa, E. A., Hsu, T., Sirota-Madi, A., Shafquat, A., Abu-Ali, G., Morgan, X. C., & Huttenhower, C. (2015). Sequencing and beyond: Integrating molecular ‘omics’ for microbial community profiling. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13(6), 360–372.

- Gaynes, R. (2017). The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(5), 849–853.

- Gupta, A., Gupta, R., & Singh, R. L. (2017). Microbes and Environment. In R. L. Singh (Ed.), Principles and Applications of Environmental Biotechnology for a Sustainable Future (pp. 43–84). Springer Singapore.

- Han, G., & Vaishnava, S. (2023). Microbial underdogs: Exploring the significance of low-abundance commensals in host-microbe interactions. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 55(12), 2498–2507.

- Hossain, M. A. (2021). CRISPR-Cas9: A fascinating journey from bacterial immune system to human gene editing. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science (Vol. 178, pp. 63–83). Elsevier.

- Huang, Y., Sheth, R. U., Zhao, S., Cohen, L. A., Dabaghi, K., Moody, T., Sun, Y., Ricaurte, D., Richardson, M., Velez-Cortes, F., Blazejewski, T., Kaufman, A., Ronda, C., & Wang, H. H. (2023). High-throughput microbial culturomics using automation and machine learning. Nature Biotechnology, 41(10), 1424–1433.

- Needs, S. H., Osborn, H. M. I., & Edwards, A. D. (2021). Counting bacteria in microfluidic devices: Smartphone compatible ‘dip-and-test’ viable cell quantitation using resazurin amplified detection in microliter capillary arrays. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 187, 106199.

- Paray, A. A., Singh, M., & Amin Mir, M. (2023). Gram Staining: A Brief Review. International Journal of Research and Review, 10(9), 336–341.

- Raghunathan, G., & Marx, A. (2019). Identification of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase variants with increased mismatch discrimination and reverse transcriptase activity from a smart enzyme mutant library. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 590.

- Song, Y., Yin, J., Huang, W. E., Li, B., & Yin, H. (2024). Emerging single-cell microfluidic technology for microbiology. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 170, 117444.

- Yu, Y., Wen, H., Li, S., Cao, H., Li, X., Ma, Z., She, X., Zhou, L., & Huang, S. (2022). Emerging microfluidic technologies for microbiome research. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 906979.

Stay updated

Get the latest first.